White Coats, Fomites, and Surrogate Endpoints

-

FROM: sensiblemed@substack.com

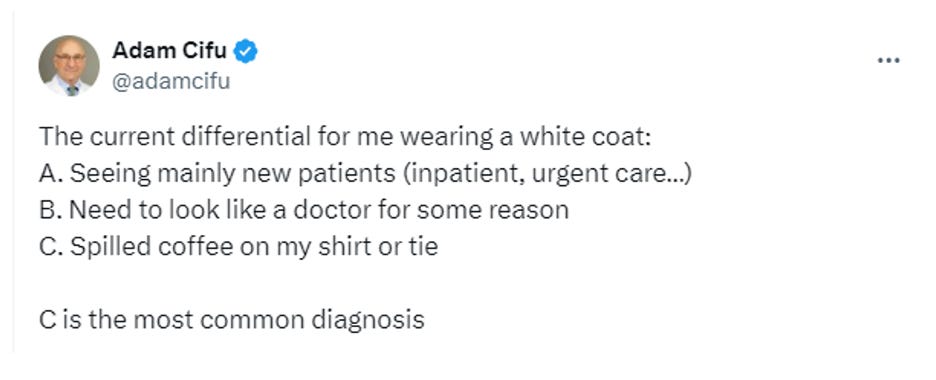

This is my second article about clothing recently. I promise I am not going to turn Sensible Medicine into a place to discuss the doctors’ style choices (“Sensible Fashion?”). However comments to my earlier article re-animated one of my pet peeves and gave me this opportunity to talk about a favorite topic, surrogate endpoints. The pet peeve is people parroting the idea that wearing a white coat or a long tie — hell, even using a stethoscope — is a major threat to public health. I hear this all the time. The sentiment is often shared with the specious statement “there is data.”¹ Here is one example, in the form of a response to what I thought was a particularly pithy tweet (from 5 years ago). You should ask yourself, what data could support, in a robust way, the concern that our white coats are a threat to our patients . You might propose a RCT, a cohort study, or a case control study.

If you have some experience with the medical literature, you have a pretty good sense that these studies don’t exist. (I reviewed the literature, it was a painful task, believe me they do not.) So, what data are people relying on to support their anti-white coat sentiments? They are referencing studies with surrogate endpoints. Some of these studies do show that there are potentially pathogenic bacteria on coats and ties. There are a few ways you might reasonably respond to these studies. You might think, “Ikk, that’s kind of gross” or “I’m sure this will make it into the lay press!” What you should not think is, “Well, those results need to change practice.” A surrogate endpoint is an objective endpoint that we can measure. Unlike clinically important endpoints, surrogate endpoints are invisible to the patient. Patients generally do not know a surrogate outcome is important until we tell them it is. Blood pressure, bone density, glycosylated hemoglobin, LDL cholesterol are the surrogate endpoints that fill my days. If surrogate endpoints are invisible, and unimportant to patients, why do we use them? We use them because it is easier to show that a treatment improves a surrogate endpoint than a clinical one. It is easier to show that a drug improves bone density than it is to show that it decreases the rate of fractures. It is easier, and far less expensive, to show that a drug lowers blood pressure than it is to show that it decreases the rate of stoke. It is easier to show that a drug lowers blood sugar than it is to show that it decreases the risk of blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks, and death. Studies with surrogate endpoints may require dozens of patients and take months to years; studies with clinical endpoints often require thousands of patients and years of follow up. The surrogate endpoints we use in research should have two qualities. First, they should be well correlated with a clinical endpoint. We know that people with lower blood sugar, better cholesterol profiles, and slower cancer progression do better than those with higher blood sugar, worse cholesterol, and more rapidly progressive cancers. Second, they should make biological sense. The problem with surrogate endpoints is that even well correlated and plausible surrogates can be misleading. We filled chapter 3 of Ending Medical Reversal with misleading surrogate endpoints. Here are a few spectacular examples.

Now you might argue here that a clean white coat is an important endpoint in itself. I agree, but we are not talking about stinking, feculent clothing here. We are talking about bacteria counts on perfectly reasonable attire, counts that might have no effect on patient outcomes. I do not actually care what anyone wears with patients, as long as they have considered how their appearance will be received by all their patients. I also do not think we should mandate clothing choices without a good reason. I should probably admit to a conflict of interest. Ever since residency, I have worn a long sleeve shirt and tie when I see patients. At the start of my career, this was because I looked like a kid, and I thought I could purchase some authority from Charles Tyrwhitt. I started to wear a white coat during the pandemic. This might have been a cognitive trick I was playing on myself to make it feel like I had an extra layer of protection. More likely it was my contrarianism — while everyone else descended into scrubs, I went hard in the other direction.⁴ Mostly, what I wear makes me comfortable and works for me with my patients. 1 Whenever people trot out the phrase “there is data”, I am reminded of the great Clash lyric from Death or Glory: Every gimmick hungry yob digging gold from rock 'n' roll Grabs the mic to tell me he'll die before he's sold But I believe in this and it's been tested by research He who f**** nuns will later join the church 2 I feel like I am channeling Dr. Prasad with that turn of phrase. Working to keep his memory alive. 3 Remember those silly videos of runners’ respiratory droplets? 4 Sarah tells me I really need to note that white coat pockets are convenient, especially if you are wearing clothes without pockets. You're currently a free subscriber to Sensible Medicine. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Views